Restoring reputations of Yorkshire Ripper’s victims after decades of victim-blaming

When Peter Sutcliffe was finally arrested in January 1981 following a five-year reign of terror involving the murders of 13 women and attacks on at least eight others, he claimed he believed he had been on a mission from God to kill prostitutes.

While it was part of his ultimately unsuccessful attempt to escape murder charges by claiming to be suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, his claim echoed almost precisely the theory that police had repeatedly put forward in their increasingly desperate hunt for him – that the so-called Yorkshire Ripper had a “pathological hatred of women he believes are prostitutes” and had made a “terrible mistake” whenever he killed anyone who was not a sex worker.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe public horror at killings involving victims being repeatedly hit with a hammer and stabbed multiple times did not prevent the persistent perception that some were less blameless than others. During Sutcliffe’s trial, prosecutor Sir Michael Havers, the then-Attorney General, controversially said while some of the victims were prostitutes, “perhaps the saddest part of this case is that some were not”.

But as two new investigations into the case now separately make clear, the still-common idea that Sutcliffe was driven by a vendetta against prostitutes was very far from the true picture. A new book by Yorkshire writer Carol Ann Lee called Somebody’s Mother, Somebody’s Daughter tells the life stories of each of his victims and explains how the majority of the Ripper’s victims actually had no connection with prostitution. Those who were are shown to often have been mothers forced into it by poverty and a desperation to feed their children, who then became targets for Sutcliffe due to their vulnerability.

The book has just been published ahead of a new BBC Four documentary series called The Yorkshire Ripper Files showing over the next three nights that lays out how police bosses’ obsession with their theory led them to repeatedly ignore or discount vital eye-witness testimony from survivors when it did not fit their premise.

Both investigations shed new light on what happened by giving voice to survivors of Sutcliffe and family members of those who were killed to paint a damning portrait of how he avoided capture for so long.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBBC documentary-maker Liza Williams says: “We were very conscious to make sure the relatives who were affected directly were able to tell their stories. The victims were judged very harshly in a lot of cases by a cross section of society. You hear it time and time again. That did shock me.

“Times have changed and attitudes have changed but there are still modern parallels. There are still cases where women aren’t listened to, where they are judged or talked about in a certain way. That still happens.”

Lee says the primary aim of her book was to highlight how Sutcliffe’s victims were much more than just statistics. “When those images of the victims flash up on television, which they often do, I want people to think ‘I know something about her’ - she was in care or she wanted to be a probation officer. They are not just victims, they had lives before and were loved by lots of people and still are.”

In the four months before his first murder, that of Wilma McCann in Leeds in October 1975, Sutcliffe had carried out three serious assaults using the same modus operandi he would employ during his killings, while none of the people he attacked – Woolworths worker Anna Rogulskyj, office cleaner Olive Smelt and 14-year-old schoolgirl Tracy Browne – had any connection to prostitution.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the latter two cases, police were given a detailed description of the attacker as a bearded man with a Yorkshire accent. But despite the similarities between the incidents – all the victims were accosted at night by a stranger before being left with severe head injuries after being hit with a blunt instrument – police did not link them together. It was to be the first of many failures in the West Yorkshire Police investigation.

Wilma McCann was attacked and killed less than 150 yards from her home on October 30, 1975, after she had been on a night out. The separated mother-of-four was initially described as having “several boyfriends” as police initially examined the possibility she had been murdered by someone she had known. As Lee explains in her book, rumours that Wilma had been selling sex to make ends meet “quickly became accepted as fact by the Press” – despite her family’s repeated insistence that it was simply untrue.

Less than three months later, Sutcliffe killed again in Leeds, taking the life of Emily Jackson. After Emily’s 14-year-old son Derek had died in a freak accident in 1969, her husband Sydney’s roofing business fell into major financial difficulties and Emily had turned to prostitution in a desperate attempt to clear their debts.

Her murder was linked to Wilma’s – leading police to put forward their theory that the “motive appears to be hatred of prostitutes” for the first time, ignoring the previous doubts about whether Wilma actually had any involvement in the sex trade. The media quickly picked up on the theory and started describing the hunt for a modern-day Jack the Ripper.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs journalist Joan Smith put it, from this point on “both evidence and suspects would be judged according to the yardstick of how well they measured up to the theory”.

On May 8, 1976, Marcella Claxton, whose family had moved to Leeds from the West Indies when she was 10, was attacked by Sutcliffe after she had left a late-night house party, surviving herself but losing the baby she was four months pregnant with. But when Marcella described her attacker as a bearded white man, police told her she was mistaken and that her attacker was black. However, the photofit she created bore a strong resemblance to the one created by Tracy Browne but was never made public as police decided there was no link to the Ripper.

On February 5, 1977, cleaner Irene Richardson, who had recently become homeless after suffering relationship and financial problems, was killed by Sutcliffe in Leeds. Sutcliffe then killed former mill worker Patricia Atkinson, who had turned to prostitution after drinking problems and the collapse of her marriage, in her Bradford flat in April 1977.

But it was not until Sutcliffe killed 16-year-old sales assistant Jayne MacDonald as she walked home from a night out on June 25, 1977, that public furore was ignited. The police described her as a “respectable young girl” who was a chance victim, while the Press said the killer had made a “terrible mistake” in contrast to his “bloodstained crusade” against prostitutes. Jayne’s family – who lived on the same street as the first murder victim Wilma McCann – were among those most angry at the division of victims into different categories of those more and less deserving of sympathy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs her sister Debra explains in Lee’s book: “I do remember Mum and Dad feeling really angry about that - the division of victims into good women and bad. It was terrible and none of us saw it that way.”

A spokeswoman for Leeds Rape Crisis Centre said at the time it was nonsense to suggest the Ripper had killed by mistake. “When you hate women as much as he must, any woman will do. Prostitutes are simply more vulnerable targets.” It was to prove an analysis more insightful and accurate than anything the police were to produce.

On July 9, 1977, 43-year-old mother-of-three Maureen Long survived being attacked by Sutcliffe after a night out. She had no link to prostitution but was described by police as a ‘woman who liked the good life’ and someone with ‘loose morals’, leading her to be labelled as such in the Press.

Sutcliffe killed again on October 1, 1977 – taking the life of mother-of-two Jean Jordan who had become a prostitute while living in poverty to feed her children.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn December 1977, Marylyn Moore, who had turned to prostitution after divorce and her children being taken into care, provided police with a description that would be later confirmed as a “remarkable likeness” of Sutcliffe after surviving an attack in Leeds. Police dismissed her as an unreliable witness but when Tracy Browne saw the photofit in the papers, she told police it was the same man who had attacked her two years earlier – only for her crucial evidence to be ignored.

Her father Tony later reflected: “If they had taken my daughter’s account seriously - and released the photofit - some of the Ripper’s victims would still be alive.”

Instead, Sutcliffe killed again little more than a month later. He murdered mother-of-two Yvonne Pearson, who had been working as a prostitute in Bradford on January 21, 1978. Yvonne had been friends with previous victim Patricia Atkinson and after her death, had carried sharpened scissors with her, fearing she would be next to be attacked. Following Yvonne’s death, a neighbour said: “She were afraid she might be the next one but she just had to go down to get food for the children.”

On February 2, 1978, Sutcliffe killed 18-year-old Helen Rytka in Huddersfield. Helen had been in care with her twin sister Rita and two other siblings after the break-up of their parents’ marriage. The twins dreamt of being pop stars but by the time they left care at 18, Helen was working at a sweet packing plant and Rita was at college. After Rita quit college, she turned to prostitution - and Helen quit her job to help her sister to work alongside her as she did not want her to be on the streets on her own.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe next victim was mother-of-seven Vera Millward who had previously worked as a prostitute and was attacked on May 16, 1978 in Manchester.

The stark division of victims by the police and Press was highlighted again following the murder of 19-year-old bank clerk Josephine Whitaker, who was attacked on April 4, 1979 as she walked back home from her grandparents’s house in Halifax. Police once again described the killing as a “terrible mistake”.

In June 1979, police revealed a tape recording of a man with a North-Eastern accent who was claiming to be the Yorkshire Ripper directly addressing Chief Constable George Oldfield. Oldfield was convinced it was the killer and the police began pouring huge resources into finding ‘Wearside Jack’. Around 40,000 people were interviewed in an attempt to find the man on the tape, subsequently revealed to be a hoaxer – while other key lines of inquiry such as trying to identify the Ripper’s car from tyre marks left at some of the murder scenes were shelved.

This came despite survivors making it clear they were certain the person who attacked them had a Yorkshire accent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the documentary, Tracy Browne describes how Oldfield himself played her the Wearside Jack tape and became ‘incensed’ when she insisted it was not the person who had attacked her.

“He was trying to put words in my mouth. But it was definitely a Yorkshire accent, not a Geordie accent in a million years,” she recalls.

Lee says: “Hindsight is the only exact science in the world but with Tracey Browne, who was only 14, the police attitude towards her was absolutely appalling.

“The descriptions by women who had survived were just cast to one side. The police said their injuries were so terrible, they couldn’t possibly remember accurately. But if that was the case, what was the point of interviewing them? Once the first two murders had occurred, the police had in their minds what the perpetrator was like.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs police pursued the Wearside Jack theory, Sutcliffe carried out five further attacks – all on women with no involvement in prostitution.

On September 1, 1979, student Barbara Leach was killed in Bradford as she walked to a friend’s party.

Civil servant Maguerite Walls was attacked and killed as she walked home after working late in Leeds on August 20, 1980. Lee’s book notes the reaction to the murder showed social judgement of women was not just reserved for prostitutes. “Her diligence led to a thinly veiled remark in the Daily Mirror on the dangers of female ambition: ‘A career woman’s devotion to work led to her murder in a savage sex attack...’,” the book records.

On September 24, 1980, Upadhya Bandara, a doctor who had just completed a postgraduate course in health service studies at Nuffield Medical Centre in Leeds, survived an attack by Sutcliffe, as did 16-year-old Theresa Sykes who was attacked in Huddersfield on Bonfire Night 1980 as she walked to the shop for cigarettes.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat would prove to be Sutcliffe’s final murder occurred on November 17, 1980 when he killed Jacqueline Hill, a Sunday school teacher, student and aspiring probation officer as she walked home from the bus stop in Leeds.

Sutcliffe was finally caught by chance in Sheffield on January 2, 1981, after being found in a car with stolen licence plates with a prostitute along with weapons he had hidden near the scene. The arrest had nothing to do with West Yorkshire Police, the force that had run the ill-fated investigation.

He had been previously interviewed by police nine times during the investigation – on one occasion being discounted because his accent did not match Wearside Jack.

Both the book and the documentary series make a conscious decision to profile the victims’ stories over that of Sutcliffe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

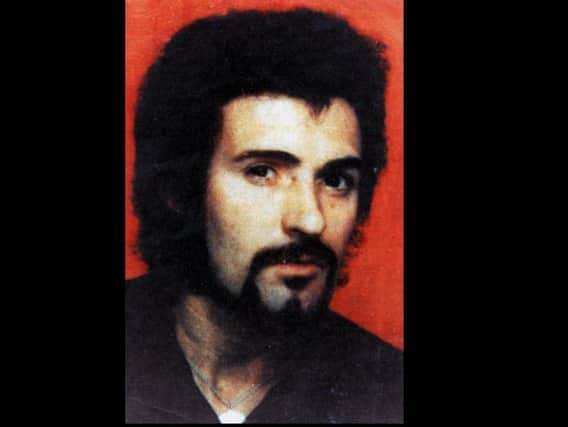

Hide AdWilliams says: “We don’t mention the killer by name until the third episode or show a photo until the third episode. They were people’s mothers, daughters, sisters, that can’t be forgotten.

We were very conscious to make sure we were telling the story of the victims.”

However, in the final episode a chilling clip of Sutcliffe blithely confessing to attacking Tracy Browne - speaking in his broad Yorkshire accent - is played.

Williams says: “As Tracy says in the film, he seems to mitigate what happened and place some level of blame on her. What is really shocking is there is no remorse at all.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Lee’s book follows a similar path to include him “as little as possible”, in its closing chapters it does include Sutcliffe’s own chilling and graphic descriptions of how he carried out each attack and murder that he admitted to.

Lee says it was a difficult choice but one she ultimately thought necessary. “I wanted primarily to focus on the women and their families and the whole time period and the way things occurred. But I thought I want to include this because it shows the kind of man he was and the horrors he inflicted.

“He deserved to be shown as the monster he really was. He still gets fan mail and people writing to him and I thought if somebody reads this, I want them to know what he did. I did a book about Myra Hindley and used her words as the things she actually said proved the kind of person she was. I wanted to do that with him.”

Lee was born in Wakefield in 1969 and although she grew up in Cornwall, would frequently visit relatives still living in Yorkshire when the attacks were taking place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“My dad’s uncle lived in these big flats in Leeds. I have really strong memories of the time, it was more of a feeling than anything else but you would see the newspaper boards outside the newsagents and hear adults talk about it. It was a sense of feeling really scared, it just felt a frightening time.

“The police were giving women mixed messages. They were telling women to look at their menfolk suspiciously but also telling them to look to them for protection.”

She says she decided to write the book after seeing the vast majority of previous ones on the topic were written by male writers and focused on either Sutcliffe or the police.

“It just seemed it is always about men and actually this case is about women, or should be. I thought it was about time women were put at the forefront of this.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“There are certain cases that capture the era and this one certainly did. While this was going on, the feminist movement was really getting stronger and in a strange way grew from how this case was handled.”

Both Lee and Williams says speaking to those directly affected by the case and examining the response of police, the media and society at the time was not easy.

Lee says: “I felt real anger more than anything and just a huge amount of sadness for these women. As the murders went on, there was the potential for this to have been stopped before it was and for him to have been caught before he was.

“I hate blaming the police but the fact of the matter is for all there was very good police work in the case, there were some terrible mistakes made on the part of the authorities. The outcome could not have been worse for these women and their families. The overwhelming feelings were anger and despair and huge sadness.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWilliams says: “I just hope that what people take from the documentary is that language does matter and the way you talk about people really matters. It is so important to listen to victims of crime.”